Getting started

With Connect, you can call remote procedures from a web browser. Unlike REST, you get a type-safe client and never have to think about serialization again.

In this guide, we'll use Connect to create a web interface for ELIZA, a very simple natural language processor built in the 1960s to represent a psychotherapist. The ELIZA service is already up and running, and it defines a Protocol Buffer schema we'll use to generate a client.

Though the Connect protocol supports all types of streaming RPCs, web browsers do not support streaming from the client side across the board. The fetch API does specify streaming request bodies, but unfortunately, browser vendors have not come to an agreement to support streams from the client—see this WHATWG issue on GitHub. This means you can use streaming from the browser, but only server streaming.

Prerequisites

- You'll need Node.js - we recommend the long-term support version (LTS).

- We'll use the package manager

npm, but we are also compatible withyarnandpnpm. - We'll use the

bufCLI to generate code. See the documentation for installation instructions.

Prepare

First, we'll configure our front end using Vite. We're

using vite to make a fast development server with built-in support for

everything we'll need later.

$ npm create vite@latest -- connect-example --template react-ts

$ cd connect-example

$ npm install

Generating the client

Next, let's generate some code from the Protocol Buffer schema for

ELIZA. We will

use generated SDKs, a feature of the Buf Schema Registry. The

first command tells npm to look up @buf packages on the registry. The install command generates

the types we need on the fly:

$ npm config set @buf:registry https://buf.build/gen/npm/v1/

$ npm install @buf/connectrpc_eliza.bufbuild_es @connectrpc/connect @connectrpc/connect-web

(You can generate code locally if you prefer. We'll explain remote and local generation after the tutorial, in the page Generating code).

Now we can import the service from the package and set up a client. Add the

following to App.tsx:

import { createClient } from "@connectrpc/connect";

import { createConnectTransport } from "@connectrpc/connect-web";

// Import service definition that you want to connect to.

import { ElizaService } from "@buf/connectrpc_eliza.bufbuild_es/connectrpc/eliza/v1/eliza_pb";

// The transport defines what type of endpoint we're hitting.

// In our example we'll be communicating with a Connect endpoint.

// If your endpoint only supports gRPC-web, make sure to use

// `createGrpcWebTransport` instead.

const transport = createConnectTransport({

baseUrl: "https://demo.connectrpc.com",

});

// Here we make the client itself, combining the service

// definition with the transport.

const client = createClient(ElizaService, transport);

Building the App

Now that you have your client all configured and working, we can hook it into a live application. We will be using React to create the user interface, but Connect is framework-agnostic and even works with vanilla Javascript.

npm run dev

This will start your web server and open the browser to the basic skeleton. Any changes to your source code will automatically refresh the browser.

Let's clear the slate of the initialized App() component:

function App() {

return <>Hello world</>;

}

The purpose of ELIZA is to represent a chat between the user and the server, so we'll want to initialize a form to facilitate communication. In this form we'll have an input and a button to submit.

function App() {

return <>

<form>

<input />

<button type="submit">Send</button>

</form>

</>;

}

This allows the user to enter some text and submit but nothing actually happens. It just refreshes the page when you click send. We need to do a few things to change that.

First, let's capture the users input and store that as state. That will allow us to control it easily:

function App() {

const [inputValue, setInputValue] = useState("");

return <>

<form>

<input value={inputValue} onChange={e => setInputValue(e.target.value)} />

<button type="submit">Send</button>

</form>

</>;

}

Hooking up the client

Next, let's capture the form submit operation and prevent refreshing the page.

Here we can also start to actually interact with our client created in the

previous step and send our

inputValue.

function App() {

const [inputValue, setInputValue] = useState("");

return <>

<form onSubmit={async (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

await client.say({

sentence: inputValue,

});

}}>

<input value={inputValue} onChange={e => setInputValue(e.target.value)} />

<button type="submit">Send</button>

</form>

</>;

}

The above is doing the bare minimum to communicate with the server and doesn't display the results from the server. We'll fix that by adding logic to track the messages sent to the server and any responses received.

const [inputValue, setInputValue] = useState("");

const [messages, setMessages] = useState<

{

fromMe: boolean;

message: string;

}[]

>([]);

return <>

<form onSubmit={async (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

// Clear inputValue since the user has submitted.

setInputValue("");

// Store the inputValue in the chain of messages and

// mark this message as coming from "me"

setMessages((prev) => [

...prev,

{

fromMe: true,

message: inputValue,

},

]);

const response = await client.say({

sentence: inputValue,

});

setMessages((prev) => [

...prev,

{

fromMe: false,

message: response.sentence,

},

]);

}}>

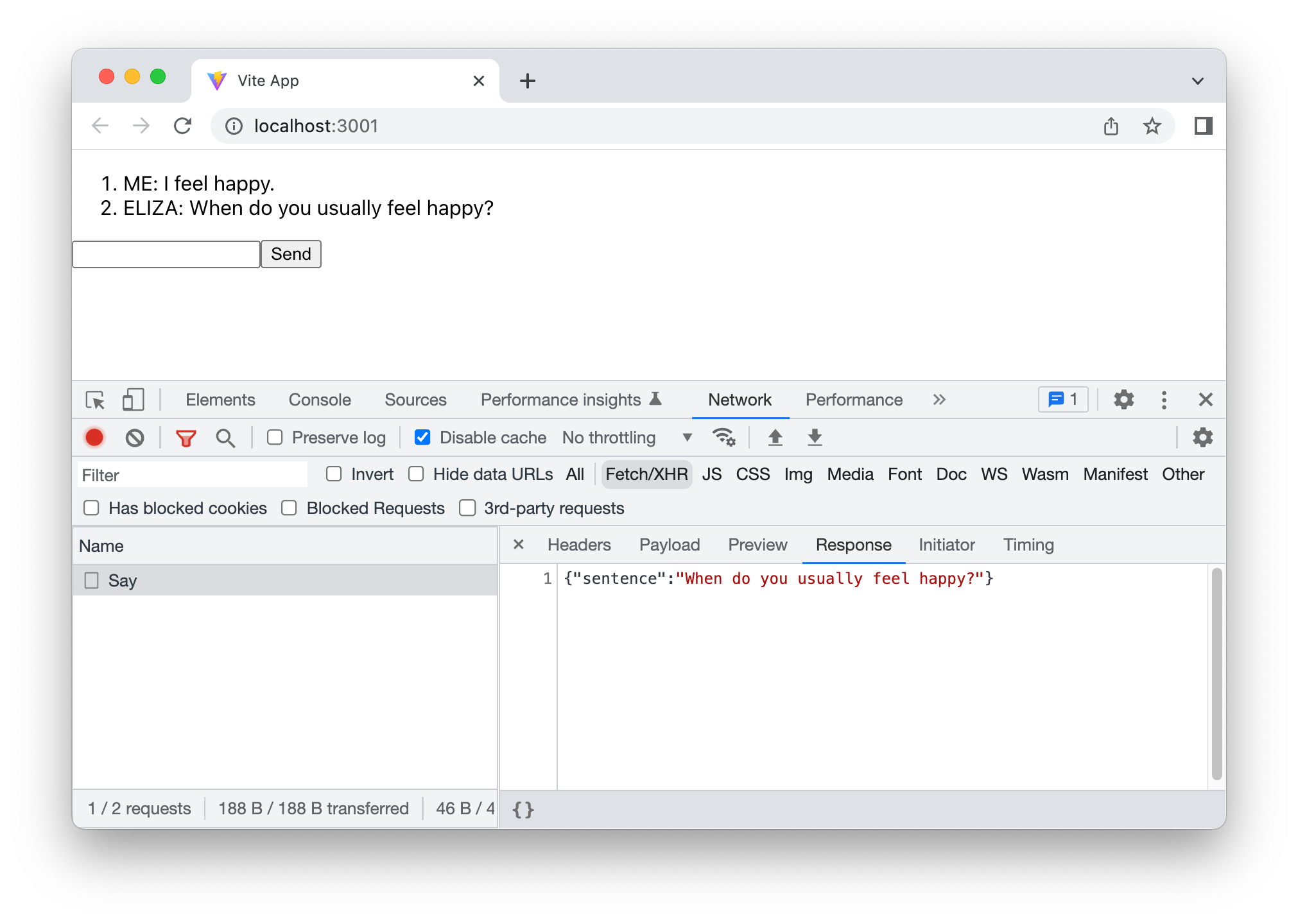

The above stores the messages but does not actually display them anywhere. We can write a simple list view to show the message chain:

return <>

<ol>

{messages.map((msg, index) => (

<li key={index}>

{`${msg.fromMe ? "ME:" : "ELIZA:"} ${msg.message}`}

</li>

))}

</ol>

<form onSubmit={async (e) => { ... }}>

</>

Wrapping up

And that's it — you've successfully made a tiny web interface for ELIZA with Vite and React.

We ran the following commands to build the app:

$ npm create vite@latest -- connect-example --template react-ts

$ cd connect-example

$ npm config set @buf:registry https://buf.build/gen/npm/v1/

$ npm install @buf/connectrpc_eliza.bufbuild_es @connectrpc/connect @connectrpc/connect-web

$ npm run dev

And wrote the following source code:

import { useState } from 'react'

import './App.css'

import { createClient } from "@connectrpc/connect";

import { createConnectTransport } from "@connectrpc/connect-web";

// Import service definition that you want to connect to.

import { ElizaService } from "@buf/connectrpc_eliza.bufbuild_es/connectrpc/eliza/v1/eliza_pb";

// The transport defines what type of endpoint we're hitting.

// In our example we'll be communicating with a Connect endpoint.

const transport = createConnectTransport({

baseUrl: "https://demo.connectrpc.com",

});

// Here we make the client itself, combining the service

// definition with the transport.

const client = createClient(ElizaService, transport);

function App() {

const [inputValue, setInputValue] = useState("");

const [messages, setMessages] = useState<

{

fromMe: boolean;

message: string;

}[]

>([]);

return <>

<ol>

{messages.map((msg, index) => (

<li key={index}>

{`${msg.fromMe ? "ME:" : "ELIZA:"} ${msg.message}`}

</li>

))}

</ol>

<form onSubmit={async (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

// Clear inputValue since the user has submitted.

setInputValue("");

// Store the inputValue in the chain of messages and

// mark this message as coming from "me"

setMessages((prev) => [

...prev,

{

fromMe: true,

message: inputValue,

},

]);

const response = await client.say({

sentence: inputValue,

});

setMessages((prev) => [

...prev,

{

fromMe: false,

message: response.sentence,

},

]);

}}>

<input value={inputValue} onChange={e => setInputValue(e.target.value)} />

<button type="submit">Send</button>

</form>

</>;

}

export default App

In case you mistype a request or response property — let's say you misspell

sentence as sentense — you are made aware of the error immediately.

As an application grows, this compile-time type-safety provided by the Protocol buffer schema becomes immensely useful. On the next page, we are going to look at the schema and explain remote and local code generation.